CP4.2 High-pressure Fuel Pump

How You Can Keep Your CP4.2 High-pressure Fuel Pump Off the Scrap Pile

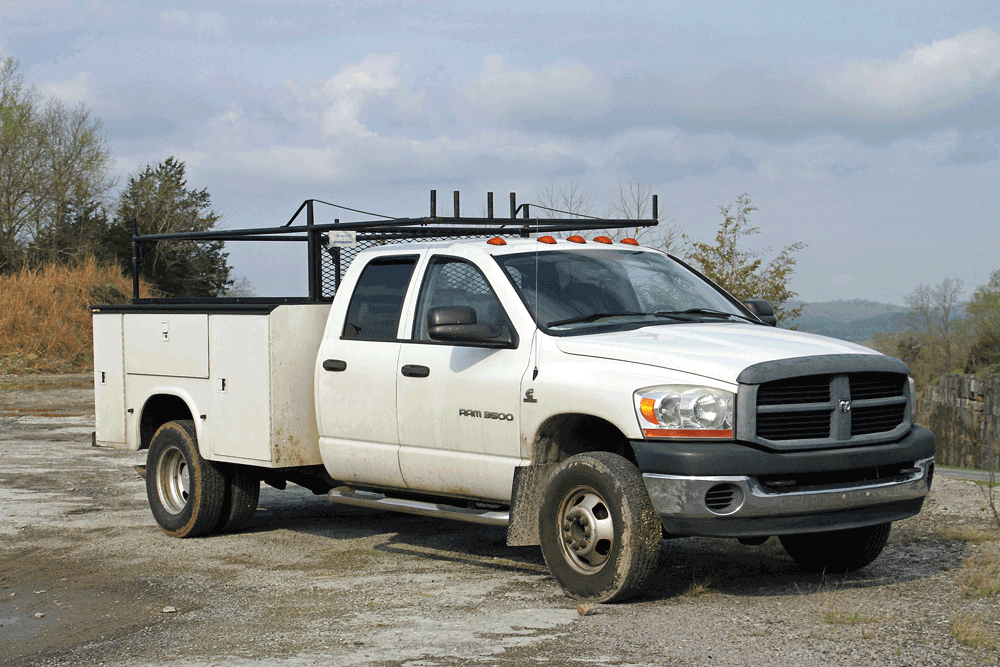

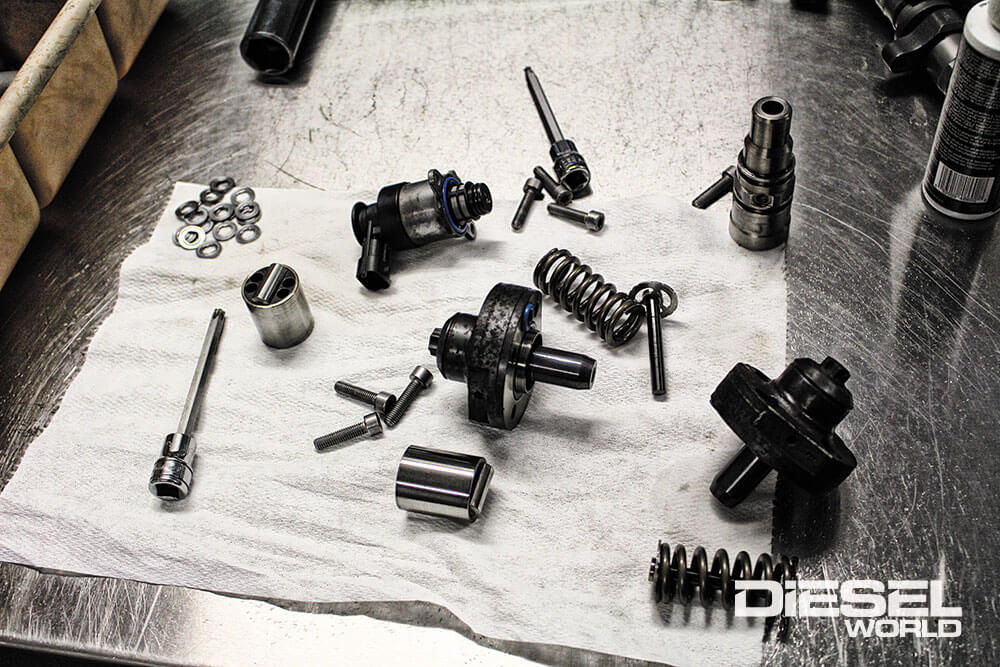

By now you’ve heard of all the problems surrounding the Bosch CP4.2, the high-pressure fuel pump that’s made its way onto most common-rail engines in the pickup truck segment. You know the story well: the pump self-destructs, sends metal fragments through the lines and rails, into the injectors, and then out the return circuit. The failure is rarely noticed before it’s too late, and by then you’re usually out a pump, lines, rails, injectors, a tank cleaning, 30 hours’ labor, and anywhere between $6,000 to $10,000. As expected, this potential catastrophe has many late-model truck owners a little uneasy about their $60,000 to $90,000 investments.

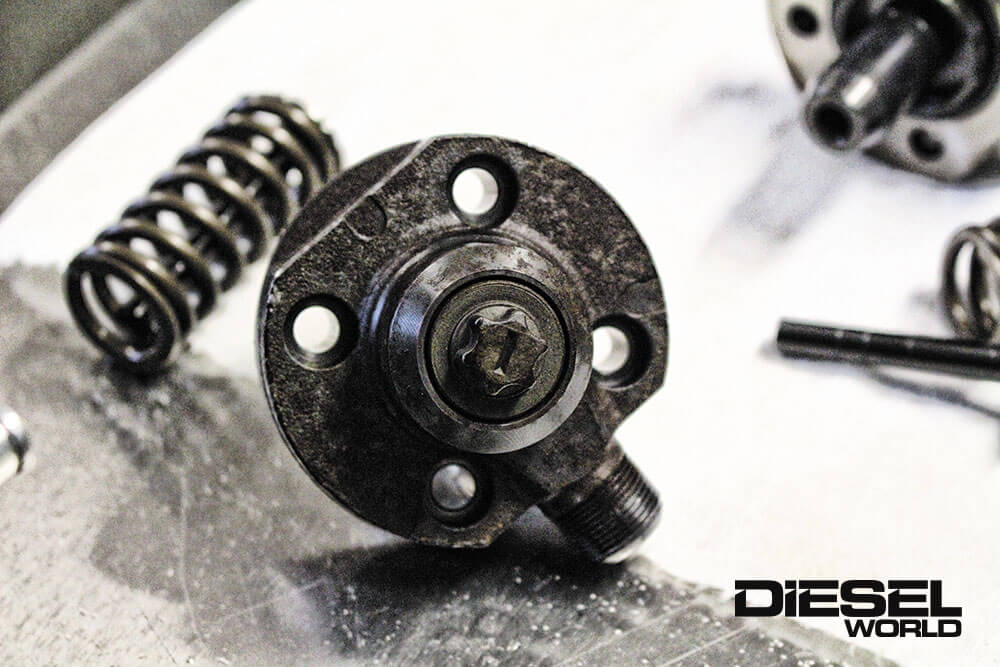

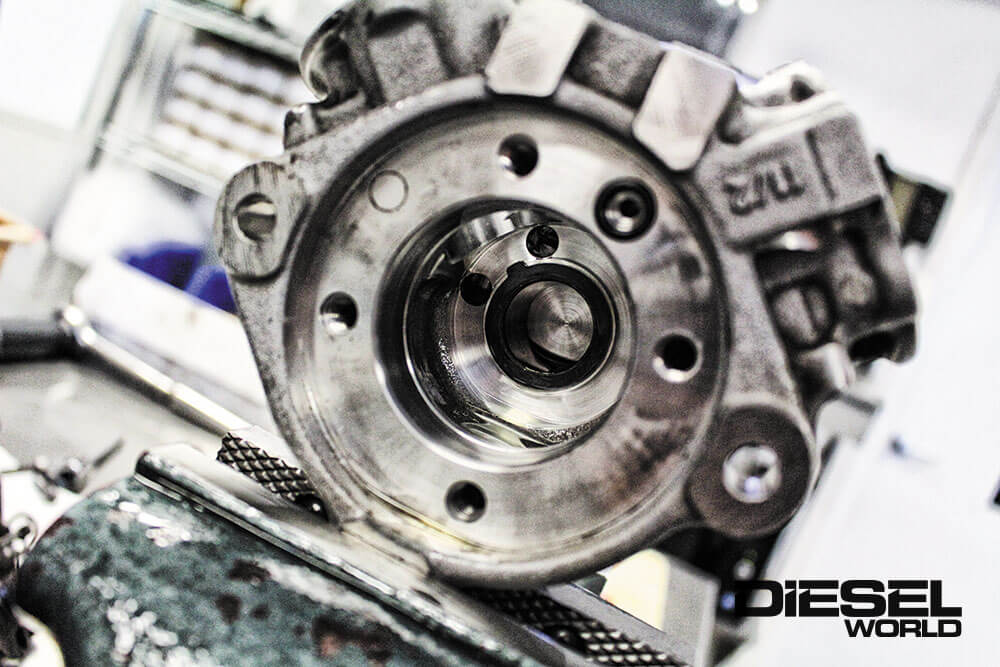

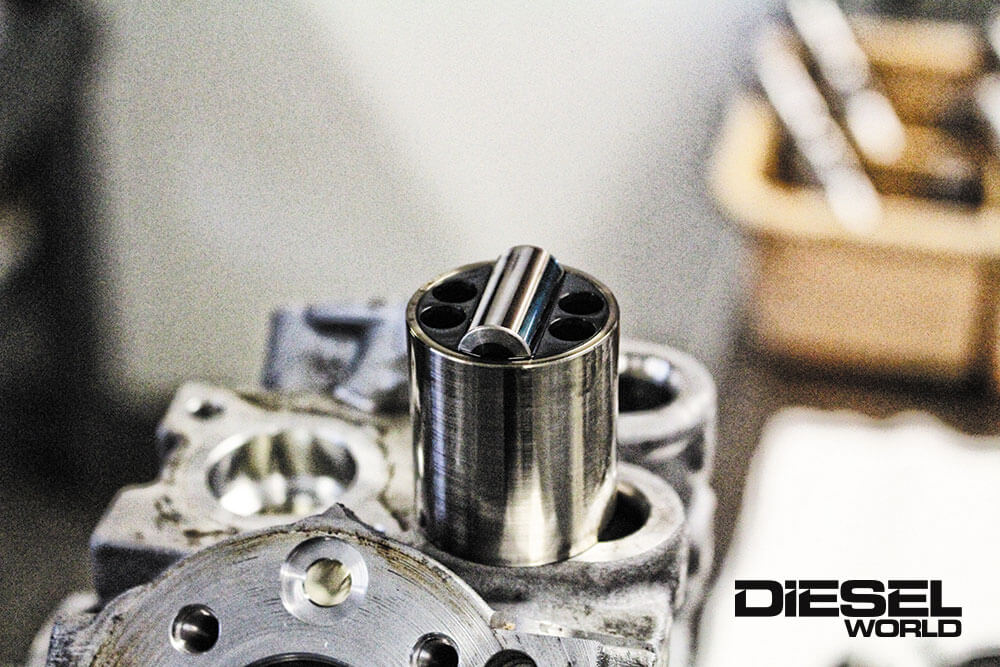

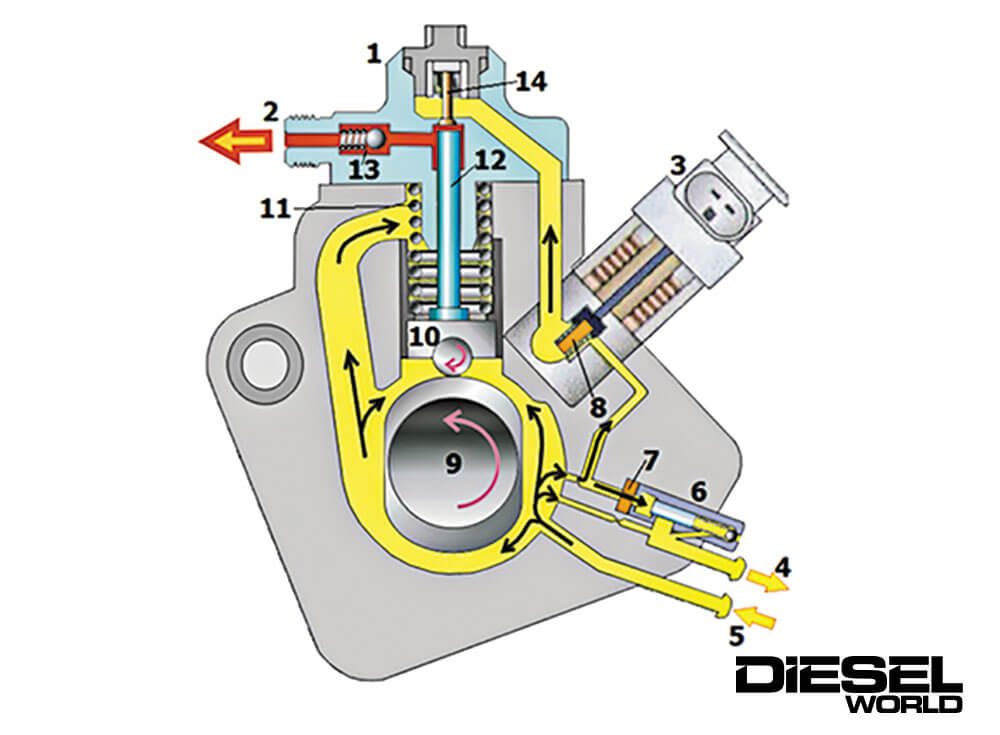

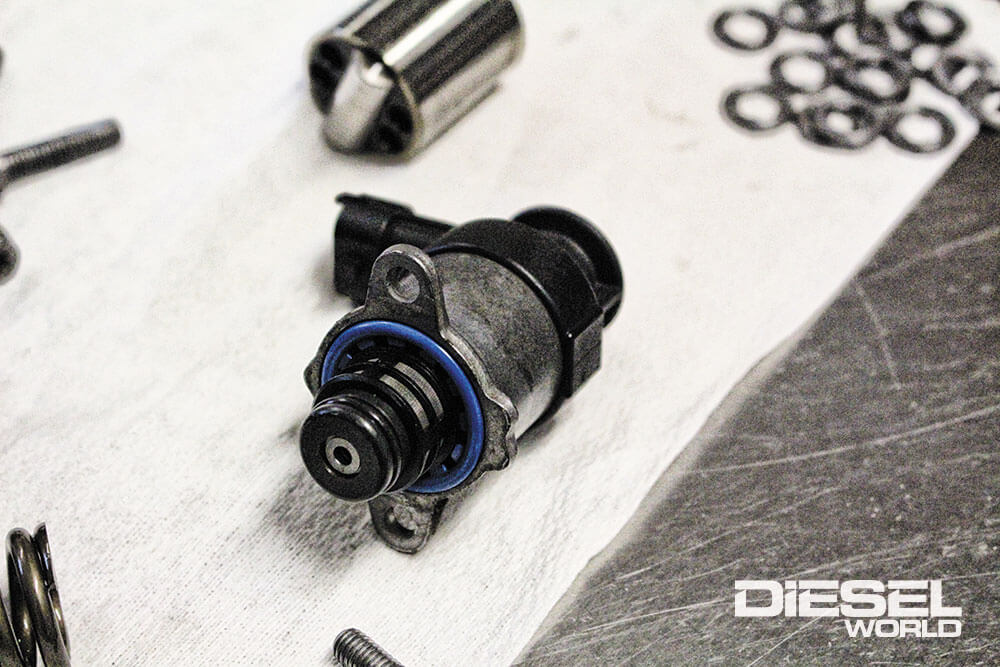

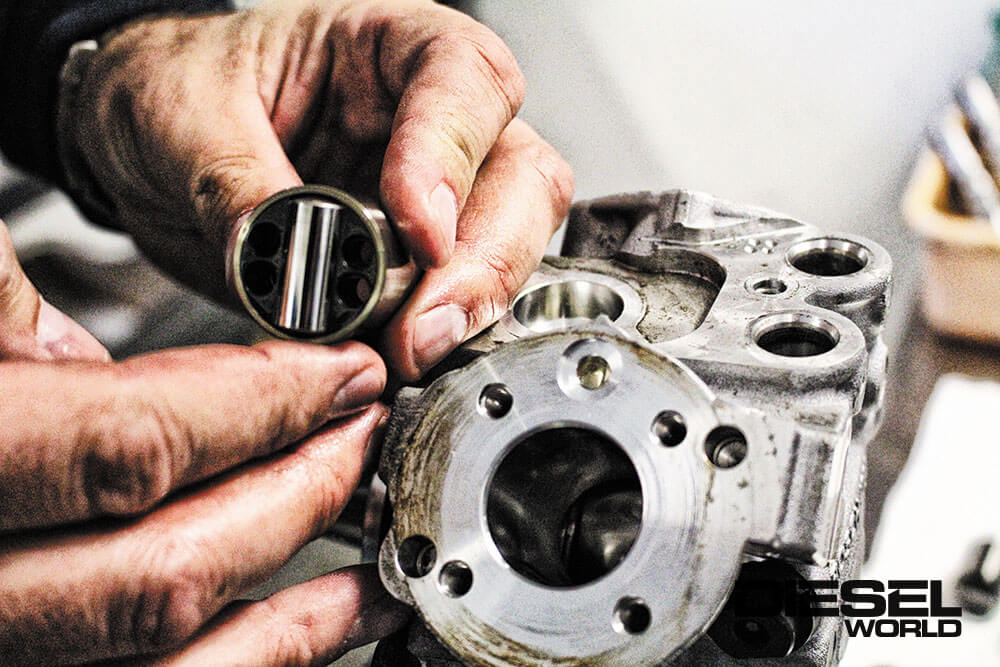

With its ultra-tight tolerances, the CP4.2 does not tolerate anything other than diesel fuel very well. But which unwanted contaminant is most common? Air. That’s right, aeration is the number one killer of these pumps. Whether it be from lack of maintenance, running the truck out of fuel, improper fuel filter installation, or not allowing the fuel system to properly prime after a filter change, nine times out of 10 this is what takes out the CP4.2. We recently stopped by RCD Performance’s state-of-the-art fuel injection shop for the full rundown on how the CP4.2 operates, what its key failure points are, and how the average truck owner can prevent it from failing.

Bosch CP4.2:

A Compact, Efficient Platform That’s Here to Stay

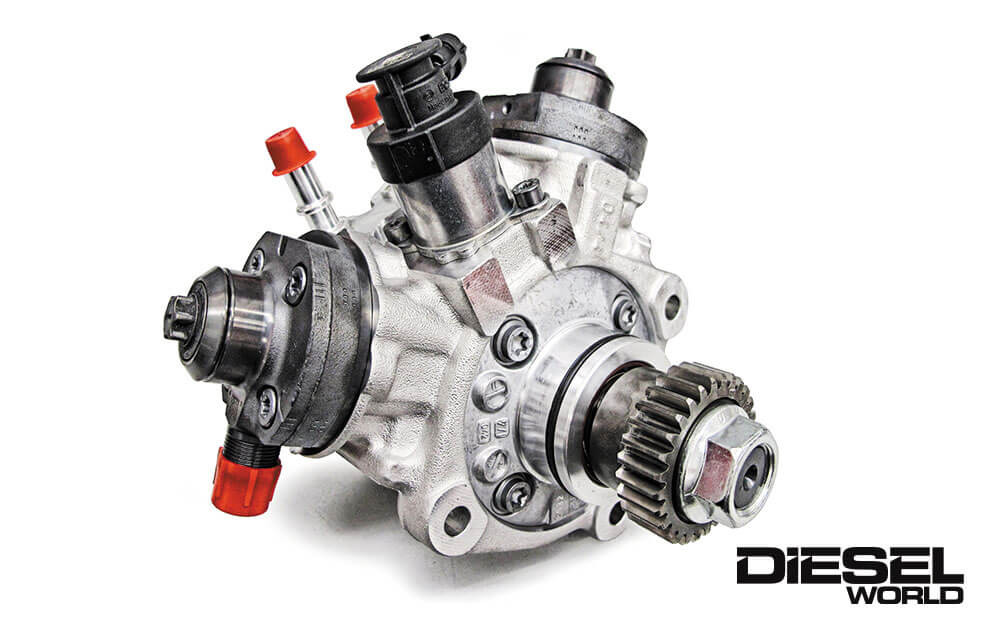

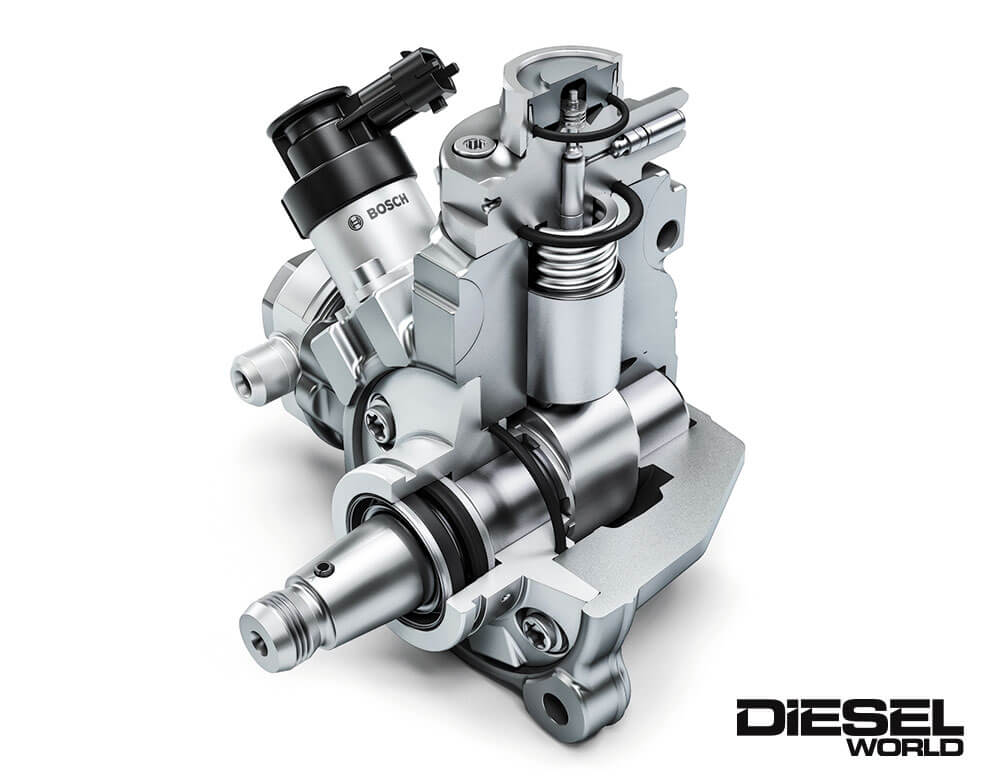

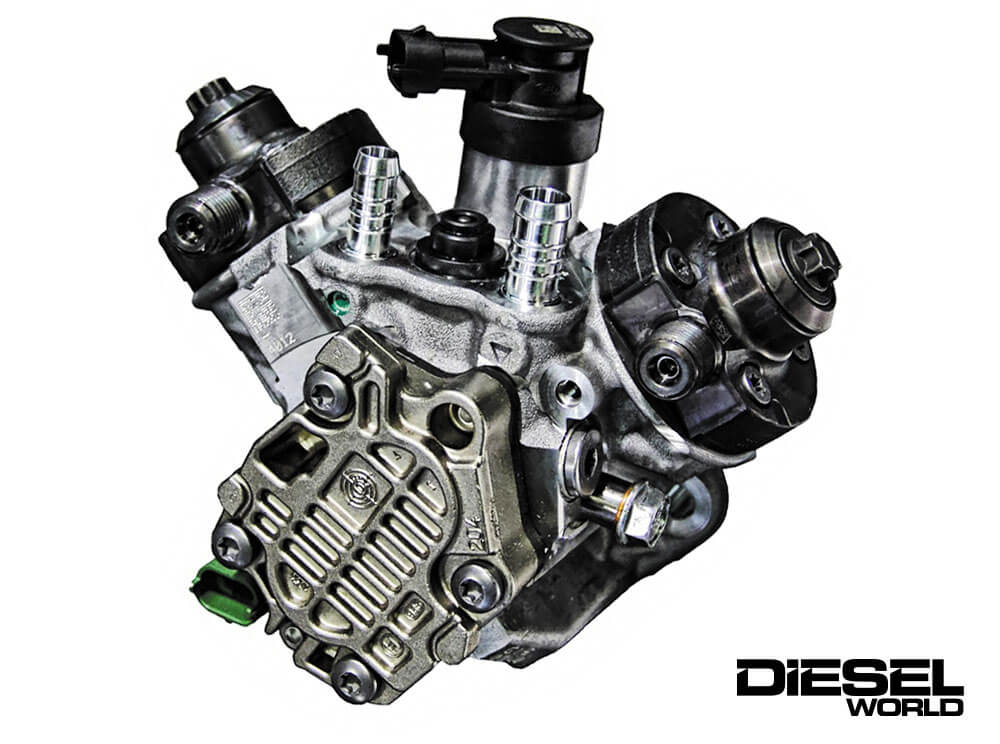

While most of us know the Bosch CP4.2 because it’s what came on our LML Duramax or 6.7L Power Stroke, this high-pressure fuel pump has been around a while. With 39,000 psi (2,700 bar) capability, the CP4 can meet even the most stringent diesel emission standards, and it’s been used in conjunction with both piezo and solenoid style injectors in dozens of passenger car makes and models all over the world. To date, more than 40 million CP4’s have been produced, with its modular design allowing Bosch to grow (CP4.2) or scale down the pump (CP4.1) based on the OE’s fuel system requirements and packaging needs.

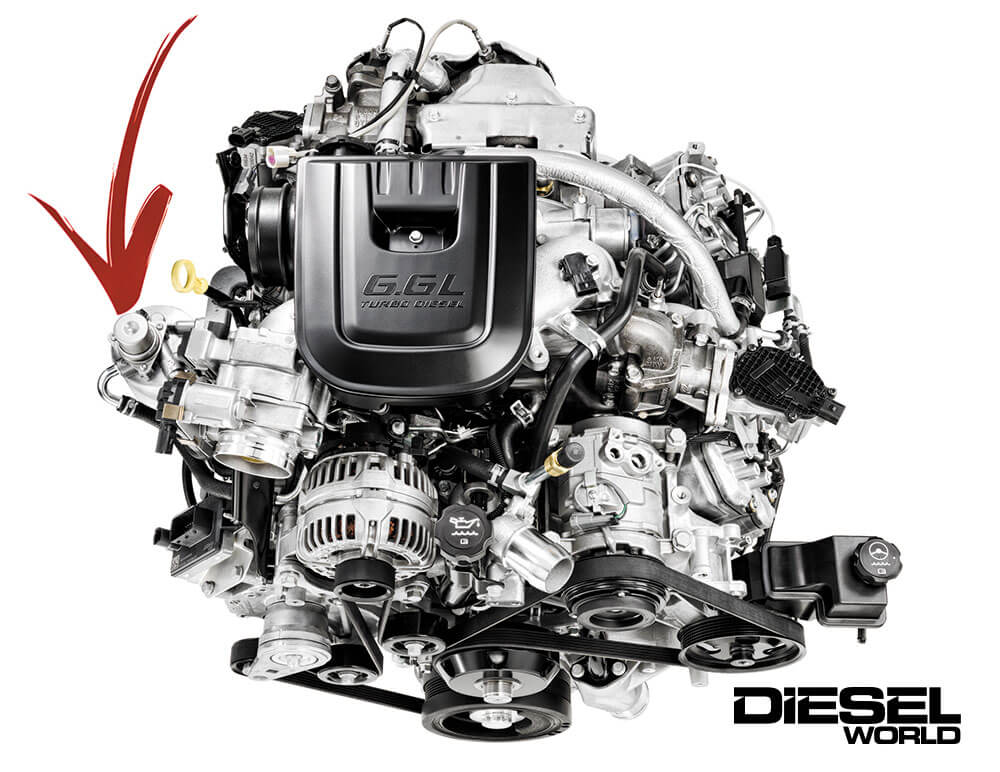

The Bosch CP4.2 debuted in the North American truck segment back in 2011 on both the 6.7L Power Stroke and the LML Duramax, although a similar version (CP4.1) had already been brought to other markets such as Volkswagen, BMW, and more than 20 other brands, globally. Fast-forward eight years and it’s in use in most diesel engines in the truck world. Though GM moved on to the Denso HP4 pump for its L5P Duramax in ’17, you can still find the CP4.2 aboard the aforementioned 6.7L Power Stroke, the 3.0L VM Motori EcoDiesel in Ram 1500’s, the 5.0L Cummins in the Nissan Titan XD, and now even the new 6.7L Cummins uses one. One thing’s for sure: this pump isn’t going anywhere any time soon.

SOURCE

RCD Performance

309.822.0600

rcdperformance.com

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS.

What is the capacity increase of the Bosch CP4.2 Fuel Pump compared to previous models?

Discover the enhanced power of upgrading your 2011-2014 6.7 Powerstroke by installing the latest high-output fuel pump. The Bosch CP4.2 fuel pump offers a significant advancement, delivering a 9% boost in capacity over earlier models. This increase means improved performance and efficiency for your vehicle.

What is the Bosch CP4.2 Fuel Pump and for which vehicle models is it designed?

While most of us know the Bosch CP4.2 because it’s what came on our LML Duramax or 6.7L Power Stroke, this high-pressure fuel pump has been around a while. With 39,000 psi (2,700 bar) capability, the CP4 can meet even the most stringent diesel emission standards, and it’s been used in conjunction with both piezo and solenoid style injectors in dozens of passenger car makes and models all over the world. To date, more than 40 million CP4’s have been produced, with its modular design allowing Bosch to grow (CP4.2) or scale down the pump (CP4.1) based on the OE’s fuel system requirements and packaging needs.

The Bosch CP4.2 debuted in the North American truck segment back in 2011 on both the 6.7L Power Stroke and the LML Duramax, although a similar version (CP4.1) had already been brought to other markets such as Volkswagen, BMW, and more than 20 other brands, globally. Fast-forward eight years and it’s in use in most diesel engines in the truck world. Though GM moved on to the Denso HP4 pump for its L5P Duramax in ’17, you can still find the CP4.2 aboard the aforementioned 6.7L Power Stroke, the 3.0L VM Motori EcoDiesel in Ram 1500’s, the 5.0L Cummins in the Nissan Titan XD, and now even the new 6.7L Cummins uses one. One thing’s for sure: this pump isn’t going anywhere any time soon.

Specific Applications

For those specifically looking to upgrade or replace their fuel injection system, the Bosch CP4.2 is designed for the 2011-2014 6.7 Powerstroke. This high-output pump offers a 9% increase in capacity, making it a popular choice for enhancing performance in these models. Additionally, it serves as a direct replacement for the 2015-2016 Ford 6.7 Powerstroke, providing flexibility and improved efficiency for a range of trucks.

Whether you’re upgrading for performance or replacing an existing component, the Bosch CP4.2 stands out as a versatile and robust option across multiple vehicle platforms.

What is the percentage increase in capacity provided by the Bosch CP4.2 Fuel Pump?

The pump offers a 9% increase in capacity.

Can the Bosch CP4.2 Fuel Pump be used as a direct replacement for newer vehicle models?

Yes, it can be used as a direct replacement for the 2015-2016 Ford 6.7 Powerstroke.

For which model years is the Bosch CP4.2 Fuel Pump designed as an upgrade?

The pump is designed as an upgrade for the 2011-2014 6.7 Powerstroke.

Can the Bosch CP4.2 Fuel Pump be used as a replacement for later Ford 6.7 Powerstroke models?

Although it’s not as common for a pump failure to occur on the 6.7L Power Stroke, if the CP4.2 does disintegrate, you’re replacing the fuel cooler and possibly even the low-pressure fuel pump in addition to the CP4.2, lines, rails, injectors, and necessary sensors.

Note: This pump can also be used as a direct replacement on the 2015-2016 Ford 6.7 Powerstroke models. This compatibility makes it a viable option for those seeking a replacement pump that fits seamlessly with these specific model years. With this assurance, you can proceed with confidence, knowing that the Bosch CP4.2 will meet the requirements for these vehicles.

Does this pump serve as a direct replacement part, or is additional modification needed?

The pump serves as a direct replacement part for the specified models, requiring no additional modifications.

Does the article specify compatibility with any other vehicles or model years?

No, the article specifically mentions only the 2015-2016 Ford 6.7 Powerstroke models for compatibility.

Is the pump compatible with the 2016 Ford 6.7 Powerstroke?

Yes, it is compatible with the 2016 Ford 6.7 Powerstroke.

Is the pump compatible with the 2015 Ford 6.7 Powerstroke?

Yes, it is compatible with the 2015 Ford 6.7 Powerstroke.

Can this pump be used as a replacement for specific Ford models?

Yes, the pump can be used as a direct replacement for the 2015-2016 Ford 6.7 Powerstroke models.

What are some compatible fuel system components and upgrades for the 6.7 Powerstroke?

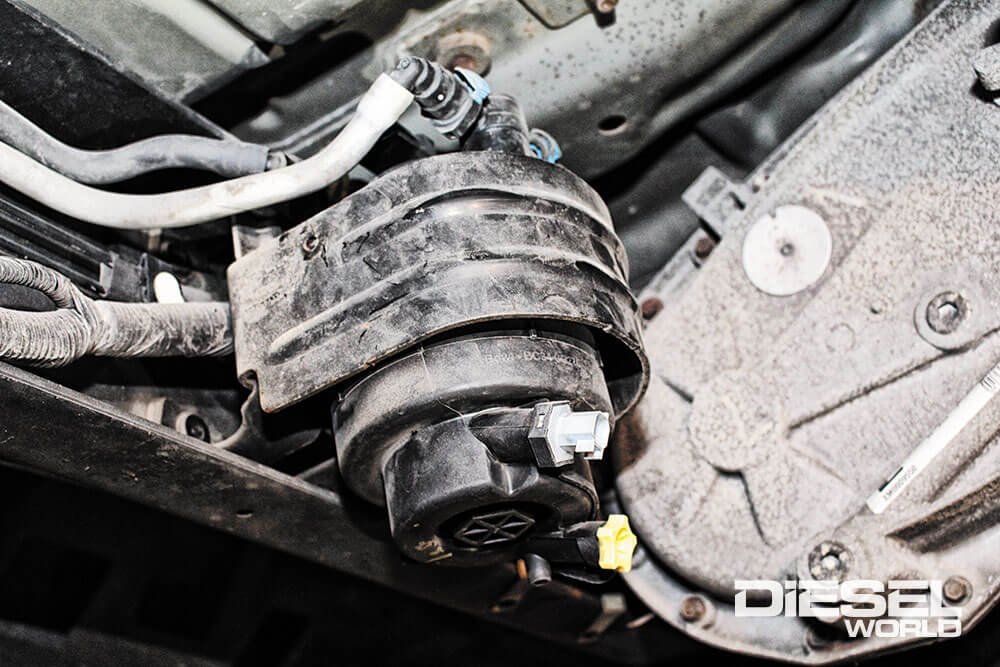

To keep the CP4.2 in a 6.7L Power Stroke happy, maintain a strict fuel filter change regimen (performed at or before Ford’s recommended interval). Make sure you change both the primary and secondary filters, ensure you install them properly, and always fill your tank with quality fuel from a safe, reputable source.

For those looking to enhance performance or replace components in their 6.7 Powerstroke, consider these compatible fuel system upgrades and replacements:

- Fuel Filters: Regular replacement of fuel filters is crucial. The AFE Proguard Fuel Filter is a reliable option for maintaining clean fuel flow.

- Fuel Systems: The AirDog II-5G Fuel System (165gph) provides improved filtration and flow, ideal for those seeking enhanced fuel delivery.

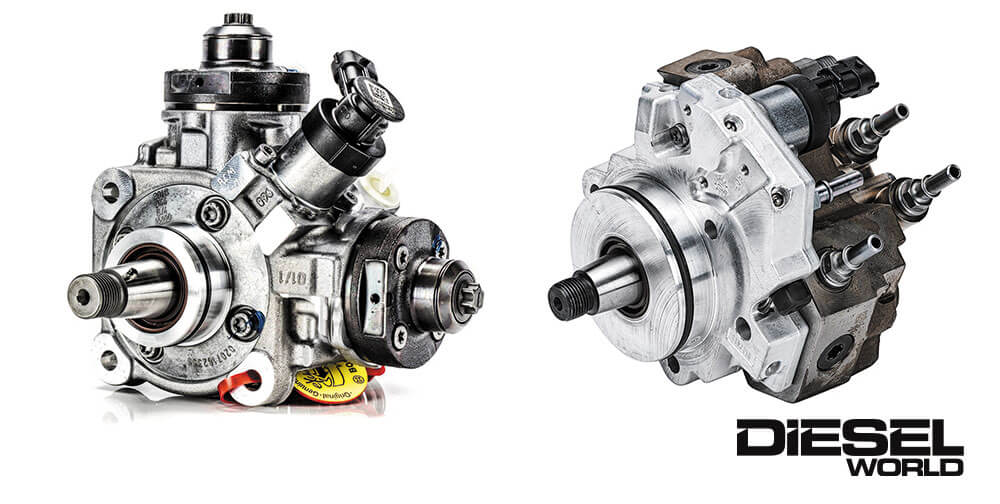

- Pumps: Upgrading to a more robust pump can make a significant difference. Options like the Exergy 10mm Stroker CP4.2 Pump or the RCD Stroker Pump 10.3MM CP4.2 offer increased durability and performance.

- Pump Conversions: The S&S CP4 to DCR Pump Conversion is an excellent choice for converting your system to a more reliable setup.

- Injectors: For precise fuel delivery, consider the DDP Individual Brand New Injector or the stock remanufactured version for various model years.

By integrating these components, you not only maintain but also enhance the performance and reliability of your 6.7 Powerstroke. Always ensure compatibility with your specific model year before purchasing.

What types of injectors are available for the 6.7 Powerstroke?

The available injectors for the 6.7 Powerstroke include brand new and remanufactured options from DDP, designed for different model years and offering stock performance replacements or upgrades.

What type of upgrades are possible for the 6.7 Powerstroke fuel system?

Upgrades for the 6.7 Powerstroke fuel system include performance enhancements such as stroker pumps and pump conversions, like the Exergy 10mm Stroker CP4.2 Pump and the S&S CP4 To DCR Pump Conversion. These can improve fuel delivery and overall engine performance.

What model years are these components compatible with?

These components are compatible with various model years of the 6.7 Powerstroke. For example, the AFE Proguard Fuel Filter is suitable for 2011-2016 models, the AirDog II-5G Fuel System for 2011-2016, and the S&S CP4 To DCR Pump Conversion covers 2011-2024.

What are the prices for these fuel system components?

The prices for these components range from $34.00 for the AFE Proguard Fuel Filter Replacement to $2,300.00 for the Exergy 10mm Stroker CP4.2 Pump. Other components are priced in between, such as the AirDog II-5G Fuel System at $880.00 and the DDP injectors, which vary from $395.74 to $487.89.

What specific components are available for the 6.7 Powerstroke fuel system?

The available components for the 6.7 Powerstroke fuel system include the AFE Proguard Fuel Filter Replacement, AirDog II-5G Fuel System, Exergy 10mm Stroker CP4.2 Pump, RCD Stroker Pump 10.3MM CP4.2, S&S CP4 To DCR Pump Conversion, and various injectors from DDP.